In the media is a fortnightly round-up of features written by, about or containing female writers that have appeared during the previous fortnight and I think are insightful, interesting and/or thought provoking. Linking to them is not necessarily a sign that I agree with everything that’s said but it’s definitely an indication that they’ve made me think. I’m using the term ‘media’ to include social media, so links to blog posts as well as as traditional media are likely and the categories used are a guide, not definitives.

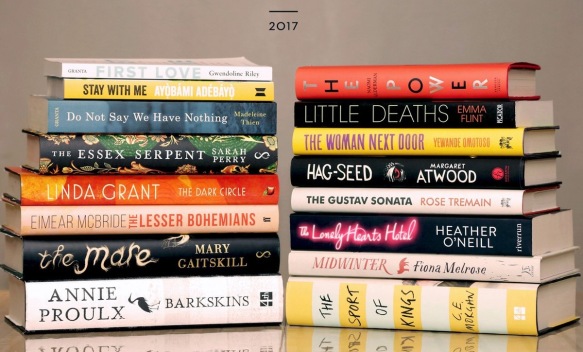

This fortnight’s seen a number of prize lists announced. The big ones for women writers are the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction longlist and the Stella Prize shortlist.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s comments on trans women have prompted a number of responses.

- Thembani Mduli, ‘When Callouts Become Anti-Black: On Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Transphobia, Disposability Culture & British Colonialism‘ on Rest for Resistance

- Rhyannon Styles, ‘The New Girl: A Trans Woman’s View Of White Male Privilege‘ in Elle

- Kuchenga Shenjé, ‘Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Transgender Comments Invalidated My Womanhood‘ on gal-dem

- Halle Kiefer, ‘Laverne Cox Responds to Chimamanda Adichie’s Comments About Trans Women and Male Privilege‘ on Vulture

- Jarune Uwujaren, ‘Why Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Comments on Trans Women are Wrong and Dangerous‘ on Unapologetic Feminism

- Racquel Willis, ‘A trans woman’s thoughts on Chimamanda Adichie‘ on Twitter

- Morgan Jerkins, ‘Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is Getting Criticized for Her Comments About Transgender Women‘ on Teen Vogue

- Hadley Freeman, ‘Identity is the issue of our age: so why can’t we talk more honestly about trans women?‘ in The Guardian

- Glosswitch, ‘The debate over Jenni Murray suggests we don’t see older women as “real women”‘ in the New Statesman

The best of the rest:

On or about books/writers/language:

- Emine Saner, ‘Books for girls, about girls: the publishers trying to balance the bookshelves‘ in The Guardian

- Lynn Steger Strong, ‘When Femininity Is Code for Feelings‘ on Literary Hub

- Caitlin Moran, ‘Were I not a writer, I’d have the peachy, zingy buttocks of Gigi Hadid’ in The Guardian

- Andreá Stella, ‘Clarice Lispector’s Children’s Story Taught Me to Read Her Like An Adult‘ on Literary Hub

- Becky Chambers, ‘My Alien Family: Writing Across Cultures in Science Fiction‘ on Tor.com

- Lorraine Berry, ‘The Man Who Doesn’t Read Women‘ on Signature

- Shaj Mathew, ‘Poetry as Life, Life as Poetry‘ on Guernica

- Jami Attenberg, ‘How Working at a Bookstore Changed My Writing Career‘ on Literary Hub

- Roxane Gay, Aimee Bender, and more ‘On Assault and Harassment in the Literary World‘ on Literary Hub

- Sophie Brown, ‘How to Escape from Prison‘ in The TLS

- Jhumpa Lahiri, ‘on the Compulsion to Translate Domenico Starnone‘ on Literary Hub

- Madeleine Wattenbarger, ‘Finding a Room of One’s Own in the Mexico City Metro‘ on Literary Hub

- Rebecca Solnit, ‘On Silence, Pornography, and Feminist Literature‘ on Literary Hub

- Alex Clark, ‘Writers unite! The return of the protest novel‘ in The Guardian

- Margaret Atwood, ‘on What ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Means in the Age of Trump‘ in The New York Times

- Casey Stepaniuk, ‘Meet Your New Favourite Darkly Comic, Magical Realist Writer: Eden Robinson‘ on BookRiot

- Margaret Atwood, ‘on What it’s Like to Watch Her Own Dystopia Come True‘ on Literary Hub

- Larissa Pham, ‘Your Own Private Party: How reading Eve Babitz got me through the depths of winter‘ on The Paris Review

- Alexandra Schwartz, ‘Rereading Paula Fox’s “Desperate Characters”‘ in The New Yorker

- Lauren Oyler, ‘How the Push to ‘Break the Silence’ Fails the Feminist Movement‘ on Broadly

- Candy Royale, ‘Ali Cobby Eckermann’s poetry: inspiring those of us who feel like outsiders‘ in The Guardian

Personal essays/memoir:

- Carolyn Desalu, ‘The Kitchen Drawer: On Black Families and Suicide‘ on Catapult

- Katherine Laidlaw, ‘A Place of Absorption‘ on Hazlitt

- Anna Graham Hunter, ‘Lying Down With Older Men‘ on Medium

- Valeria Luiselli, ‘On the Choices People Make in Coming to America‘ on Literary Hub

- Nicole Cox, ‘Proper Young Ladies: Writing My Mother’s Shakespeare Essay‘ on Medium

- Funmi Iyanda, ‘Theory of Death” In Conversation with My Mother‘ on Medium

- Elisabeth Fairfield Stokes, ‘Life and Breath: On Pregnancy and the Spirit World‘ on Catapult

- Keph Senett, ‘A Bed of Fists: On Playing Soccer in Moscow‘ on Catapult

- Ashley P. Taylor, ‘Für Bess: On Neighbors, Music Parties, and Growing Up‘ on Catapult

- Jessica Furseth, ‘I Don’t Have Cancer (Yet)‘ on Buzzfeed

- Darcy Steinke, ‘How I Came to the Church of Rock and Roll‘ on Literary Hub

- Jessie Male, ‘Mirror Pain‘ on Guernica

- Nicole Chung, ‘The Worry I No Longer Remember Living Without‘ on Hazlitt

- Nneka Onwuzurike, ‘My Mother’s Name‘ on The Offing

Feminism:

- Rachel Vorona Cote, ‘The Misogynistic History of Trying to Understand Women Who Self-Harm‘ on Broadly

- Liza Munday, ‘Why Is Silicon Valley So Awful to Women?‘ on The Atlantic

- Zoe Williams, ‘Cuts are a feminist issue. So what would a suffragette do?‘ in The Guardian

- Erin Vanderhoof, ‘How the Combative Beginning of Women’s Studies Shaped Feminist In-Fighting Today‘ on Broadly

- Arianna Rebolini, ‘Heads Up, ‘Slimming’ Is Not a Compliment‘ on Racked

- Jendella Benson, ‘Patriarchy and The Idealisation Of Motherhood‘ on Media Diversified

- Han Yujoo, ‘Misogyny blooming and the universal feminine‘ on The TLS

- Rebecca Solnit, ‘Silence and powerlessness go hand in hand – women’s voices must be heard‘ in The Guardian

- Jia Tolentino, ‘The Women’s Strike and the Messy Space of Change‘ in The New Yorker

- Joanna Cannon, ‘How to embody the “Be Bold For Change” ethos‘ on The Pool

- Maxine Beneba Clarke, ‘My Feminism‘ on Victoria Women’s Trust

Society and Politics:

- Jess Phillips, ‘I feel sorry for the people of Tatton – I hear their MP is just too busy to care‘ in The Guardian

- Amelia Tait, ‘Joining Generation Rent isn’t a quirky choice – it’s our unavoidable state of economic insecurity‘ in the New Statesman

- Ijeoma Oluo, ‘Welcome To The Anti-Racism Movement — Here’s What You’ve Missed‘ on The Establishment

- Molly Ball, ‘Kellyanne’s Alternative Universe‘ on The Atlantic

- Vera Chok, ‘If you saw a nanny in this BBC interview, what does that say about you?‘ in The Guardian

- Molly Ball, ‘Washington’s Spy Paranoia‘ on The Atlantic

- Julie Beck, ‘This Article Won’t Change Your Mind‘ on The Atlantic

- Sara Noviç, ‘The Right to Remain Silent‘ in The New Enquiry

- Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi, ‘“I want to try. Live or die”: how refugees decide whether to make the dangerous trip to Europe‘ in the New Statesman

- Sarah Menkedick, ‘The Making of a Mexican-American Dream‘ on Pacific Standard

- Renata Adler, ‘Brontosaurs Whistling in the Dark‘ in Lapham’s Quarterly

- Alana Semuels, ‘The Racist History of Portland, the Whitest City in America‘ on The Atlantic

Film, Television, Music, Art, Fashion and Sport:

- Kate Robertson, ‘Why Female Cannibals Frighten and Fascinate‘ in The Atlantic

- Sophie Gilbert, ‘Is Girls Heading Toward a Conventional Happy Ending?‘ on The Atlantic

The interviews/profiles:

- Katie Kitamura in The Guardian

- Rachel Cusk in The Cut

- Jami Attenberg on The Millions, Vogue and Electric Literature

- Rebecca Solnit in Elle

- Ann Goldstein on Hazlitt

- Delia Bell Robinson on Bloom

- Can Xue on Words Without Borders

- Ariel Levy on Longreads and Jezebel

- Ahd Niazy on The Establishment

- Elif Batuman on Vulture and Publishers Weekly

- Megan Bradbury in The Skinny

- Allison Benis White on Electric Literature

- Gwendoline Riley on The Skinny

- Sawako Nakayasu on Asymptote

- Chris Kraus on Ssense

- Angie Thomas in The Bookseller

- Danielle Dutton on Catapult

- Claudia Roden on Food52

- Susan Hill on Waterstones

- Dorthe Nors on The Writes of Woman

- Sharon Olds on Literary Hub

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in The Guardian

- Ursula K. Le Guin in The TLS

- Judith Kerr in The Guardian

The regular columnists:

- Lucy Mangan in Stylist

- Roxane Gay in The Guardian US

- Yasmin Alibhai-Brown in The Independent

- Caitlin Moran in The Times

- Lauren Laverne in The Pool

- Ella Risbridger in The Pool

- Sali Hughes in The Pool

- Bim Adewunmi in The Guardian

- Sophie Heawood in The Guardian

- Eva Wiseman in The Observer

- Tracey Thorn in The New Statesman

- Chimene Suleyman and Maya Goodfellow on Media Diversified

- Josie Pickens on Ebony

- Bridget Christie in The Guardian

- Lizzy Kremer on Publishing for Humans

- Juno Dawson in Glamour

- Kashana Cauley on Catapult

- Louise O’Neill in the Irish Examiner

- Jendella Benson on Media Diversified

- Lola Okolosie in The Guardian

- Sarah Gerard, ‘Mouthful‘ on Hazlitt

- Books by Women We’d Love to See in English on Literary Hub