It’s 2016 and in Lark, Texas two bodies have been found within a week. The first, a black male, a visitor to the town. The second, a local white woman. It’s the talk of Geneva Sweet’s cafe:

“And ain’t nobody done a damn thing about that black man got killed up the road just last week,” Huxley said.

“They ain’t thinking about that man,” Tim said, tossing a grease-stained napkin on his plate. “Not when a white girl come up dead.”

“Mark my words,” Huxley said, looking gravely at each and every black face in the cafe. “Somebody is going down for this.”

Locke introduces Texas Ranger, Darren Mathews into the equation. Mathews is suspended from duty and his marriage is on the rocks over an ultimatum issued by his wife who wants him to quit his job. His suspension is due to him being called out late at night by a friend, Rutherford McMillan, over an incident with Ronnie Malvo. Two days later, Malvo was found dead. The bullet wounds matched McMillan’s gun, a gun which he’d reported missing the previous day.

Ronnie “Redrum” Malvo was a tatted-up cracker with ties to the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas, a criminal organization that made money off meth production and the sale of illegal guns – a gang whose only initiation rite was to kill a nigger. Ronnie had been harassing Mack’s granddaughter, Breanna, a part-time student at Sam Houston State, for weeks – following her in his car as she walked to and from town, calling out words she didn’t want to repeat, driving back and forth in front of her house when he knew she was home, cussing her color, her body, the way she wore her “nappy” hair.

When Mathews gets a call from his friend Greg Heglund, an agent within the Houston field office of the FBI, telling him about the case in Lark and suggesting he go and find out why the local sheriff’s refusing outside help, Mathews can’t help himself.

In Lark, Locke creates a town dominated by the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas and the power and money of Wally Jefferson. A man who lives in a house which is a near perfect replica of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and sits bang opposite Geneva’s cafe. Bluebird, Bluebird is a tale of racial hatred but Locke’s created something much more complex than the initial premise appears. As Mathews uncovers the town’s secrets, Locke shows how the heritage of blacks and whites in America is deeply entwined and suggests that white hatred comes from a more complicated place than they might wish to acknowledge.

Bluebird, Bluebird is a gripping, timely novel. The first in a new series featuring Darren Mathews, I’m already looking forward to the next instalment.

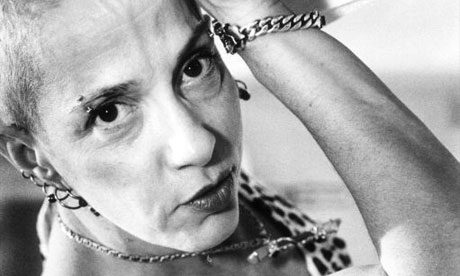

I’m delighted to welcome Attica Locke to the blog to answer some questions about the book.

Bluebird, Bluebird has a contemporary setting; did it feel important to be writing about race in America now?

It’s simply my world view. I’m a person of color and so I frequently write characters who are of color and in portraying the contemporary world they live in, I end up writing about race in America. I will say that I wrote this book before Trump was elected and we’ve seen this ugly cancer of racism metastasize all over the country. So it’s been odd seeing how prescient the book is. Although…. Just the fact that Trump was running for President of the United States so successfully was hint enough as to where we were headed.

A small section of the novel is written from the point of view of a white supremacist; how did it feel to get into the mindset of that character?

Oddly freeing. It wasn’t hard to write at all. I just typed up all my worst nightmares about what white supremacist think of me and let it all out. Somewhere in there too I was trying to understand where all that rage comes from. I have a theory that so much of hate and crime has to do with people’s perceived concept of scarcity—their belief, often false belief, that there isn’t enough for them. I think Keith—that character—believes that black men have taken something from him. It’s really a wounded point of view. It actually, I hope, shows you how small these white supremacists are.

The relationships you portray, particularly the marriages, are complex and often difficult. What interests you about people’s romantic relationships?

I suppose the usual stuff—what draws people together. It’s always interesting to write two people who don’t seem like they should be drawn to each other but they are anyway. And of course romantic conflict can be so irrational and passionate. That’s always fun to write too.

Why did you choose to write crime fiction?

It goes to what I was saying before. It’s a mix of exploring what scares me and also philosophically looking at the way people respond to perceived scarcity—whether scarcity of money of love and affection. I’m so curious about why some people lash out and some people don’t.

You’re a screenwriter as well as a novelist; do you treat them as separate entities or does your work in one form inform your work in the other?

I think they can’t help but inform each other—maybe in ways I can’t even see. But I understand the two mediums very well and I treat them differently when I’m writing.

Are we going to see more of Ranger Darren Matthews?

Yes! This is the beginning of a series of novels along Highway 59 in east Texas, all featuring Darren Mathews.

And, I have to ask, will Jay Porter be back at any point?

I’m sure. But it’s nothing I’d try to force. I’d have to wait for the right story to demand that he return.

My blog focuses on women writers; who are your favourite female writers and have you read anything recently by a woman writer that you’d recommend?

Jane Smiley. Toni Morrison. Francine Prose. Jesmyn Ward. Paula Daly. Liane Moriarty. Curtis Sittenfeld. Tayari Jones. Jami Attenberg.

My favourite books of the last 18 months or so are All Grown Up by Jami Attenberg; Swing Time by Zadie Smith; Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng; Made for LoveMade for Love by Alisa Nutting; Woman No. 17 by Edan Lepucki; and Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman.

Thanks to Attica Locke for the Q&A and to Serpent’s Tail for the review copy.

![FullSizeRender[3]](https://thewritesofwoman.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/fullsizerender3.jpg?w=143&h=202)

![FullSizeRender[2]](https://thewritesofwoman.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/fullsizerender21-e1451496678778.jpg?w=130&h=196)

![FullSizeRender[1]](https://thewritesofwoman.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/fullsizerender1.jpg?w=584&h=227)

![FullSizeRender[4]](https://thewritesofwoman.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/fullsizerender4.jpg?w=300&h=236)