When the Goldsmiths Prize shortlist was announced, there were two books I was thrilled to see on the list. One was Martin John by Anakana Schofield and the other was Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun by Sarah Ladipo Manyika. Both books made a huge impression on me when I read them earlier in the year. I’ve re-read them both since and I stand by my initial thoughts, they’re both brilliant. I’m absolutely delighted then to have had the opportunity to interview Sarah Ladipo Manyika, who, I hope you’ll agree, gives good interview.

Your protagonist, Dr. Morayo de Silva, is glorious: turning 75, well-travelled, well-educated, lives alone, aware of her sexuality, drives a sports car, dresses in colourful clothes and planning her first tattoo. Where did she come from?

Toni Morrison is quoted as saying that if there’s a book you want to read that hasn’t yet been written, than you must write it yourself. This was what drove me to write Morayo’s story. I was finding plenty of books about older men but few about older women and even fewer about the lives of black women. Yet, all around me I kept meeting older women who’d led colourful lives. There was my neighbour, an opera singer in her eighties, who upon seeing my handsome, septuagenarian father inquired as to whether he was single. He wasn’t, but that didn’t stop her fancying him. And then there is my 95-year-old Zimbabwean relative who recently acquired her first cell phone and keeps it hidden in a bright blue purse tucked into her bra. When the phone rings, she announces to the world, “phone ringing,” but doesn’t bother to answer. She simply enjoys the sound of it ringing. Another woman that inspired my writing was a single, elderly Jewish woman, whom I met when I first moved to San Francisco. She was not as flamboyant as many others that I’d met, but she was just as fiercely independent. The last few years of her life were difficult ones and so I wrote this story – a more upbeat story, one that I would perhaps have wished for her.

Sarah with her 95-year-old relative

I believe that all books are in conversation with books that came before. And because Morayo’s books are in a very real sense her friends, her conversation with them is an embodiment of such conversations. Morayo, like me, is particularly attuned to some of the gaps in literature – to those voices and characters, that don’t often appear. Morayo, as an elderly black woman in San Francisco, is one such person. I find myself drawn to characters that are invisible due to socioeconomic status, age, gender and ethnicity. I’m particularly interested in how the so-called “outsiders” think of themselves in contrast to how others see them.

The story’s told from multiple viewpoints, which is some feat for a novella. How did you manage this so the reader wasn’t jolted from the story by a shifting perspective?

When I first started writing this story, I wrote it in the third person, but after some time, my characters grew tired of being represented by the omniscient third person and walked off the page in protest.

“Enough with the ‘he said’ and ‘she said’,” they announced in a cacophony of multiple firsts.

“Absolutely not!” I said. “This isn’t The Sound and the Fury! You’re just a short novel, so how can I possibly have you all talking in the first person. Readers will just get confused.”

“Says who?” asked my main character.

“Convention!”

“Convention?” she scoffed, “But aren’t you the one that keeps saying that people like us hardly appear in literature? Why keep restraining us then?”

“We’re just trying to be helpful,” replied Morayo’s best friend.

“Yeah,” added another of Morayo’s friends, “and personally, I’m tired of people looking at me like I need pity ‘n shit. So if you don’t wanna hear our voices, count me out.”

The novella’s dense with themes – age, the lack of understanding people have of other people’s cultures, homelessness, women’s roles – how did you ensure the story didn’t collapse under them?

I wrote the book, leading with character rather than theme. In this way, I let the themes emerge organically. There were times, however, when some of my personal concerns threatened to sink parts of the narrative. I was writing this book at a time when videotapes of police brutality against black men and women filled the news. I was, and still am, angry and horrified by the persistence of racism and police brutality in America and elsewhere. I quickly realized, however, that Morayo’s story was not the place to vent my personal frustrations. While racism inevitably features in the novel, I chose the vehicle of nonfiction to address racism more fully.

You published your first novel In Dependence with UK publisher, Legend Press, but Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun is published by Cassava Republic, an African Press. Was it a conscious decision to go with an African publisher?

Yes, it was a conscious decision to choose Cassava Republic Press, a publishing company based out of Nigeria and now the U.K. I realized that by granting world rights to an African publisher I could, in a small way, attempt to address the imbalance of power in a world where the gatekeepers of literature, even for so-called African stories, remain firmly rooted in the west. Also, when I presented Cassava Republic Press with my manuscript, a novella, they didn’t shy away from a genre that is currently perceived by its European and American competitors as an “awkward sales and marketing proposition”. Being shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize is an honour that I share with my publishers.

How do you feel about the novella being shortlisted for The Goldsmiths Prize?

I’m delighted, thrilled, happy as lark, and also still stunned … a bit like a mule that’s over the moon and on cloud nine, surprised to find her load of ice cream, still intact. And what an honour to be shortlisted with such an incredible group of writers! The beauty of prizes is that it expands a writer’s readership. All of a sudden I have readers that I wouldn’t otherwise have heard of my work. It’s particularly exciting to be shortlisted for a prize that rewards the unconventional. Many people told me that a short novel wasn’t a good idea, that it wasn’t advisable to frequently switch viewpoints, not to mention writing a story about an older black woman. Who would read it?

What’s next? Are you working on anything you can tell us about?

I’m currently working on some nonfiction. San Francisco has a large homeless population and this is one of the things I’m writing about.

My blog focuses on female writers; who are your favourite female writers?

Several years ago, when I realized how few women writers I’d read, I decided to rectify that. I started with Marilynne Robinson’s Home, and what a treat that book was – so deceptively quiet, so deeply profound. I then eagerly raced through books by Toni Morrison and Virginia Woolf and revelled in these authors’ ability to write so confidently while experimenting with form and style. I also enjoyed the way these authors depicted the so-called “ordinary” and domestic spheres of life in a way that I found fresh and exciting. Since then I’ve been racing to catch up on what I’d been missing. I’m grateful for blogs such as The Writes of Woman that feature and highlight women’s voices. I don’t have favourite writers but I do have favourite books. Here are some current favourites:

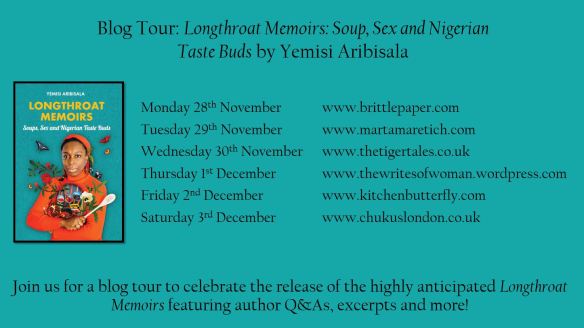

Longthroat Memoirs: Soup, Sex, and Nigerian Taste Buds – Yemisi Aribisala

We Need New Names – NoViolet Bulawayo

Mr. Loverman – Bernardine Evaristo

Things I Don’t Want to Know – Deborah Levy

Home – Toni Morrison

Happiness Like Water – Chinelo Okparanta

The Face – Ruth Ozeki

Citizen – Claudia Rankine

Lila – Marilynne Robinson

The Diver’s Clothes Lie Empty – Vendela Vida

The Paying Guests – Sarah Waters

Huge thanks to Sarah Ladipo Manyika for the interview.