The Electric Michelangelo– Sarah Hall

The Electric Michelangelo– Sarah Hall

I started the year re-reading my favourite book. For those of you at the back, that’s The Electric Michelangelo by Sarah Hall. It tells the story of Cy Parks: his childhood in Morecambe, raised in his mother’s B&B; his apprenticeship to Eliot Riley, the local tattoo artist, and his journey to New York, where he sets up a booth in Coney Island and meets Grace, a woman from war-torn Eastern Europe, who asks him to decorate her body. Throughout the book there’s discussion about women’s bodies and what they’re allowed to do with them but it’s Grace who seems to have the answer:

It will always be about body! Always for us! I don’t see a time when it won’t. I can’t say you can’t have my body, that’s already decided, it’s already obtained. If I had fired the first shot it would have been on a different field – in the mind. All I can do is interfere with what they think is theirs, how it is supposed to look, the rules. I can interrupt like a rude person in a conversation.

I’m not going to give anything away about whether or not she succeeds, I’ll just mention again that it’s my favourite novel of all time and leave you to do the right thing.

My Sister the Serial Killer– Oyinkan Braithwaite

My Sister the Serial Killer– Oyinkan Braithwaite

Ayoola summons me with these words – Korede, I killed him.

I had hoped I would never hear those words again.

Ayoola, as you can see, has a thing for murdering men, men she’s dated who’ve become angry with her. Korede’s good with the bleach so helps with the clean-up. Two things are about to become a problem though: Femi, the man Ayoola kills at the beginning of the book, has family who want to know what’s happened to him, and Ayoola starts dating Tade, a doctor at the hospital where Korede’s a nurse. A doctor Korede also has a crush on.

Braithwaite examines the role of the patriarchy in the way women behave, both towards men and towards each other. She asks whether we can ever escape our childhoods and if blood really is thicker than water. A smart page turner.

Thanks to Atlantic for the review copy.

Louis & Louise– Julie Cohen

Louis & Louise– Julie Cohen

Louis and Louise, Cohen’s protagonists, are the same child, born to the same parents, in the same place, at the same time. But they are born as two different sexes. Cohen then jumps forward 32 years to show us how their lives have turned out. Lou(ise) is a teacher and single mother to her daughter, Dana, living and working in Brooklyn. Lou(is) is a writer who’s in the process of splitting up with his wife. In both timelines, Lou is summoned home to Casablanca, Maine, because their mother is dying of cancer. This means a confrontation with Allie, Lou’s former best friend, and the uncovering of secrets kept for over a decade.

What I was expecting from Louis & Louise was a critique of gender from the protagonist’s perspective, a ‘look what you could’ve won’ style narrative. But Cohen’s version is more sophisticated than that; she uses the twins, Allie and Benny, Lou’s childhood best friends to explore the restrictions binary gender places on both women and men. There are points where this isn’t a comfortable read [cn for domestic violence, rape and suicide] but Cohen shows that there might be another way. There are a number of points in the book where Louis and Louise’s stories meet. These sections are written as though the character is non-binary, using singular they for their pronoun, and show that some of this person’s experience was identical, regardless of gender. Both versions also end with hope. Louis & Louise is a sophisticated look at gender and love and is well worth your time.

Thanks to Orion for the review copy.

Baise-Moi – Virginie Despentes (translated by Bruce Benderson)

Baise-Moi – Virginie Despentes (translated by Bruce Benderson)

On Sundays, I’ve started giving myself free rein to read whatever I want from my poor, neglected shelves. You know, those books I bought because I wanted to read them that sit there while I go through proofs and reading for work. Woe is me and the books that never get read. I was so enamoured with Despentes’ Vernon Subutex 1 that I’ve bought everything that’s been translated and decided to start from the beginning.

Baise-Moi translates as Rape Me so let me insert all of the trigger warnings here. Nadine is a sex worker who watches pornography incessantly. Manu has a huge appetite for sex and alcohol. After Manu is raped and Nadine kills her flatmate, the two women’s paths cross and they embark on a killing spree. It seems superfluous to mention it really, but this isn’t for the faint hearted. It’s violent, full of sex and swearing, but also – dare it say it – gripping. There’s an element of excitement in watching two women do something men have dominated for years. Morality aside, of course. Thelma & Louise meets Natural Born Killers.

The Mental Load – Emma (translated by Una Dimitrijevic)

The Mental Load – Emma (translated by Una Dimitrijevic)

Emma went viral with the comic ‘You Should’ve Asked’ a couple of years ago. The Mental Loadis a collection of her pieces dealing with gender and political issues, ranging from working in a hostile environment to forced caesarean sections to the male gaze to raids on immigrants made under the guise of terrorism laws. The strips are informative, clear and interesting. However, it felt a little feminism/capitalism 101 to me, in which case, I’m not the intended audience. I do heartily recommend that every heterosexual man reads a copy asap though, but not at the expense of doing his share of the housework or childcare.

You Know You Want This – Kristen Roupenian

You Know You Want This – Kristen Roupenian

Roupenian went viral last year with her story ‘Cat Person’ which was published in The New Yorker. Much has been made of the subsequent high figure deals she then netted for this, her debut collection. I mention it more because it’s become a talking point that as an indicator for how to read the stories – the collection seems to have taken a battering in some quarters because it isn’t what the reader expected it to be on the basis of one story and some publishing money.

If you’re looking for more stories in the same vein as ‘Cat Person’ you get one; ‘The Good Guy’ is the longest story in the collection and tells the story of Ted, who thinks he’s good but is clearly bad. Ted’s one of those men who thinks that because he had female friends, because he was the nice guy who hung around listening to their problems while working out how he might shag them, he’s good. Roupenian (and the rest of us) have news for Ted.

The rest of the stories take a somewhat darker turn. If you were expecting Sally Rooney, prepare for Ottessa Moshfegh without the redeeming qualities. In ‘Bad Boy’ a couple who have a friend staying in their flat know he can hear them having sex, so persuade him to join them; in ‘Sardines’ Tilly makes a birthday wish that will please her mum but cause problems for her dad and his new, younger girlfriend; in ‘Scarred’ the narrator conjures up her heart’s desire to discover that maybe it’s not what she wanted after all. When Roupenian’s at her best, she makes your skin crawl: ‘The Matchbox Sign’, in which Laura discovers bite marks on her skin which her doctor thinks are psychosomatic, made me itch, while ‘Biter’, in which Ellie does what it says, made me wince (and maybe punch the air, a little bit). You Know You Want This isn’t a perfect collection but it’s an interesting one.

Thanks to Jonathan Cape for the review copy.

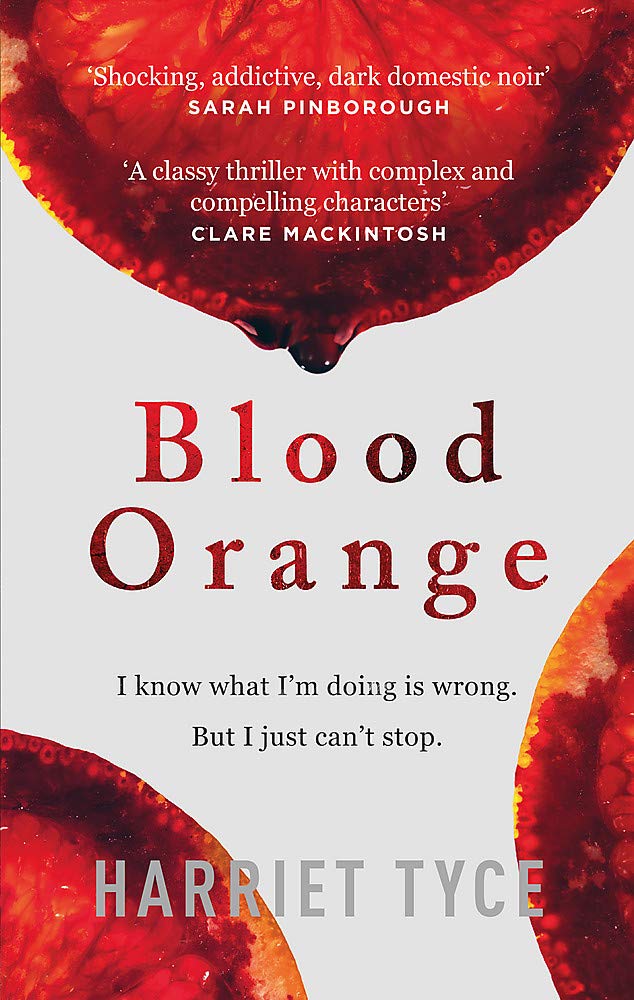

Blood Orange – Harriet Tyce

Blood Orange – Harriet Tyce

Madeleine Smith is found next to her husband’s body; he’s been stabbed to death in their bed. Madeleine says she’s guilty but there’s something about her story that doesn’t quite seem right.

Alison is going to take Madeleine’s case – her first murder case, but Alison’s got problems of her own: she’s drinking too much, having an affair with a colleague and someone knows. Her husband, Carl, is a therapist who’s had enough of Alison’s drinking and late nights at work and isn’t afraid to use their daughter, Matilda, to make Alison feel guilty.

Tyce tells the story from Alison’s perspective and – as we follow her thoughts and actions – it starts to become clear that something isn’t quite right.

Because this is a psychological thriller and therefore some of the enjoyment hinges on the twists, I don’t want to say too much more about the plot. However, Tyce takes a very topical look at the behaviour of men and finds them wanting. Blood Orange is fierce, smart, gripping and sticks a very big middle finger up at the patriarchy. Obviously, I loved it.

Thanks to Wildfire for the review copy.

The Electric Michelangelo– Sarah Hall

The Electric Michelangelo– Sarah Hall My Sister the Serial Killer– Oyinkan Braithwaite

My Sister the Serial Killer– Oyinkan Braithwaite Louis & Louise– Julie Cohen

Louis & Louise– Julie Cohen Baise-Moi – Virginie Despentes (translated by Bruce Benderson)

Baise-Moi – Virginie Despentes (translated by Bruce Benderson) The Mental Load – Emma (translated by Una Dimitrijevic)

The Mental Load – Emma (translated by Una Dimitrijevic) You Know You Want This – Kristen Roupenian

You Know You Want This – Kristen Roupenian Blood Orange – Harriet Tyce

Blood Orange – Harriet Tyce