In the media is a fortnightly round-up of features written by, about or containing female writers that have appeared during the previous fortnight and I think are insightful, interesting and/or thought provoking. Linking to them is not necessarily a sign that I agree with everything that’s said but it’s definitely an indication that they’ve made me think. I’m using the term ‘media’ to include social media, so links to blog posts as well as as traditional media are likely and the categories used are a guide, not definitives.

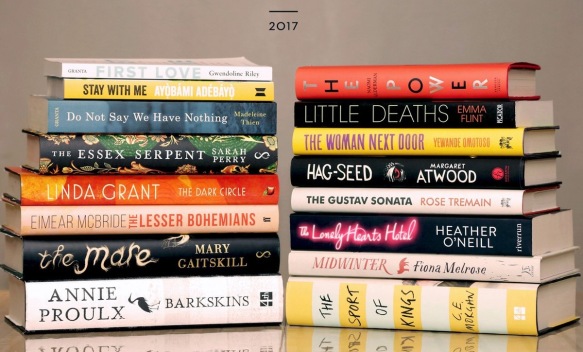

In prize news, the Granta Best of Young American Novelists list was announced:

- Laura Miller, ‘Granta Made Us Obsessed With “Best Young Novelist” Lists‘ on Slate

- Michelle Dean, ‘The age of anxiety: what does Granta’s best young authors list say about America?‘ in The Guardian

Fiona McFarlane took The Dylan Thomas Prize for her short story collection The High Places, Maylis de Kerangal won The Wellcome Book Prize, and Sarah Perry and Kiran Millwood-Hargrave were winners at The British Book Awards. While Kit de Waal and Rowan Hisayo Buchanan were shortlisted for The Desmond Elliott Prize.

Chris Kraus and I Love Dick are having a moment:

- Kraus is interviewed in The Guardian and on Hazlitt with Sarah Gubbins

- Rachel Syme, ‘The Liberating Obsessiveness of I Love Dick‘ in New Republic

- I don’t usually link to book reviews but ‘Reviewing this book put me off marriage. And book reviewing‘ by Anakana Schofield is a brilliant piece of writing in its own right and is about Kraus’ novel Torpor.

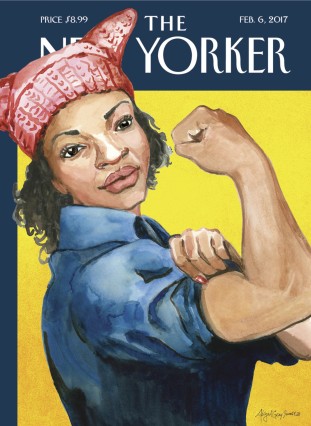

And The Handmaid’s Tale has generated even more pieces:

- haettinger, ‘I Grew Up In A Fundamentalist Cult — ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Was My Reality‘ on The Establishment

- Megan Garber, ‘The Handmaid’s Tale Treats Guilt as an Epidemic‘ on The Atlantic

- Priya Nair, ‘Get out of Gilead: Anti-Blackness in The Handmaid’s Tale‘ on Bitch Media

- Kayla Chadwick, ‘The Biggest Lesson Of The Handmaid’s Tale? Silence Is Complicity.‘ on the Huffington Post

- Nora Caplan-Bricker, ‘One Sly Lesson of The Handmaid’s Tale:Appreciate the Messy Feminism We Have Now‘ on Slate

- Elizabeth Day, ‘What the Handmaid’s Tale taught me about being a woman‘ on The Pool

- Laura Hudson, ‘The Handmaid’s Tale: The Biggest Changes From the Book‘ on Slate

- Alexandra Schwartz, ‘Yes, “The Handmaid’s Tale” Is Femininst‘ in The New Yorker

- Soraya Nadia McDonald, ‘In “Handmaid’s Tale” a postracial, patriarchal hellscape‘ on The Undefeated

- Various, ‘“Margaret Atwood Made a Feminist Out of Me”: 12 Authors on The Handmaid’s Tale‘ in Elle

- Stacey D’Erasmo, ‘On Power Between Women: The Handmaid’s Tale Revisited‘ on Catapult

- Jamie Lincoln, ‘The Handmaid’s Tale: The Hidden Meaning in Those Eerie Costumes‘ on Vanity Fair

The best of the rest:

On or about books/writers/language:

- Emily Gould, ‘My Bad Parenting Advice Addiction‘ on Longreads

- Jenny Landreth, ‘Water Women: Jenny Landreth’s Swell and the Female Swimmers Who Changed the World‘ on the Waterstones’ blog

- Heather Corcoran, ‘One thing Amazon got wrong about “I Love Dick” (and women)‘ on Slate

- Judith Newman, ‘Dear Book Club: It’s You, Not Me‘ in The New York Times

- Susanna Basso (translated by Matilda Colarossi) ‘Lessons in Slowness‘ on Asymptote

- Rafia Zakaria, ‘The Lizzie Borden murder industry won’t die – but its feminism has‘ in The Guardian

- Elizabeth Alsop, ‘What Ferrante learned from Woolf‘ in The TLS

- Caren Lissner, ‘That Time a Guy Asked Me to Channel My Novel’s Protagonist On Our Creepy First Date‘ on Narratively

- Barbara Browning, ‘The Lie in My Novel‘ on Catapult

- Sarah Menkedick, ‘The Blue Jay’s Dance‘ in The Paris Review

- Sarah Menkedick, ‘The Book and the Baby‘ on Vela

- Meghan Daum, ‘What Makes a House a Home‘ on Literary Hub

- Alexandra Schwartz, ‘The Art and Activism of Grace Paley‘ in The New Yorker

- Kathryn Hughes, ‘George Eliot: is this a new portrait of the author as a young woman?‘ in The Guardian

- Lisa McInerney, ‘Don’t tell me that working-class people can’t be articulate‘ in The Guardian

- Emily Ballaine, ‘Bookselling in the 21st Century “Please Don’t Touch Me”‘ on Literary Hub

- Lisa Ko, ‘Not Finishing My Novel Would’ve Ruined My Life‘ on Literary Hub

- Hope Nicholson, ‘The fury and the fashion: comic-book heroines down the years‘ in The Guardian

- Helena Kelly, ‘The Many Ways in Which We’re Wrong About Jane Austen‘ on Literary Hub

- Jenni Fagan, on her path to publication on Dewar Art Awards

- Lorraine Berry, ‘on Didion, the South, and Race‘ on Essay Daily

- Rachel Rhys, ‘on writing a community of strangers‘ on The Literary Sofa

- Sarah Hughes, ‘‘She gave her mother 40 whacks’: the lasting fascination with Lizzie Borden‘ in The Guardian

- Nicola Streeten, ‘Drawn from history‘ in The TLS

- Sydney Moore, ‘Were women accused of witchcraft the first Essex Girls?‘ on The Pool

- Ever Dundas, ‘The Problems with Gender and Language‘ on The Skinny

- Danuta Kean, ‘Crossing the Line of Duty: why novels would never get away with TV’s crimes‘ in The Guardian

- Claire Cameron, ‘Why You Shouldn’t Get into a Fight with Jane Smiley‘ on Literary Hub

- Sunny Singh, ‘MP accuses BAME book prize of discrimination‘ on Media Diversified

- Kristen Arnett, ‘The Queer Erotics of Handholding in Literature‘ on Electric Literature

- Danuta Kean, ‘Why Brit crime fiction is paying international dividends‘ in The Guardian

- Nell Stevens, ‘Elizabeth Gaskell: Charlotte Brontë’s unlikely defender against prurient gossip‘ in The Guardian

- Sisonke Msimang, ‘All your faves are problematic: A brief history of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, stanning and the trap of #blackgirlmagic‘ on Africa Is a Country

- Rafia Zakaria, ‘A publisher of one’s own: Virginia and Leonard Woolf and the Hogarth Press‘ in The Guardian

- Laura Lam, ‘Gender-fluid Fiction: False Hearts Author on Breaking Stereotypes‘ on Waterstones’ Blog

- Dani Shapiro, ‘Writing About Marriage When You Want to Stay Married‘ on Catapult

Personal essays/memoir:

- Linda Mannheim, ‘Searching for the Internment Camp Where My Father Was Held‘ on Catapult

- Sarah Maria Griffin, ‘This Is What It’s Like To Have Sleep Paralysis‘ on Buzzfeed

- Caity Weaver, ‘My 14-Hour Search for the End of TGI Friday’s Endless Appetizers‘ on Gawker

- Ashley C. Ford, ‘My Father Spent 30 Years In Prison. Now He’s Out.‘ on Refinery29

- Eva Dillon, ‘My Father’s Secret Life as a Cold War Spy‘ on Literary Hub

- Stacy Torres, ‘The Admission‘ on Longreads

- Lisa Ko, ‘How I Learned To Live With A Chronic Skin Condition‘ on Buzzfeed

- Laura Turner, ‘On Miscarriage, Anxiety, and the Burden of Hope‘ on Catapult

- Julia Kingsford, ‘Aspergers and Asparagus‘ on Medium

- Sari Botton, ‘Hit Eject‘ on Longreads

- Kat Lister, ‘It’s essential that I tell you about my miscarriage‘ on The Pool

- Marie Myung-Ok Lee, ‘J. Stands Up‘ in The Paris Review

- Erin Chack, ‘My Boyfriend Isn’t My Soulmate, He’s My Carrot‘ on Buzzfeed

- Jennifer Hope Choi, ‘I Filmed The End Of My Parents’ Marriage‘ on Buzzfeed

- Zing Tsjeng, ‘My 14-Year-Old Cousin Taught Me How to Be a Cool Teen‘ on Broadly

- Betty Ann Adam, ‘How I lost my mother, found my family, recovered my identity‘ in Saskatoon Star Phoenix

- Clarissa Wei, ‘The Struggles of Writing About Chinese Food as a Chinese Person‘ on Munchies

- Lyz Lenz, ‘Lead Me On‘ on Hazlitt

- Eloghosa Osunde, ‘Don’t Let It Bury You‘ on Catapult

- Erin Kelly, ‘Learning to be a red lipstick kind of person‘ on The Pool

- Elisabeth Geier, ‘The Nostalgia of the Neighborhood Hardware Store‘ on Okey-Panky

Feminism:

- Nimco Ali, ‘I’m a Women’s Equality Party candidate – here’s why I’m standing against a female Labour MP‘ on The New Statesman

- Jess Zimmerman, ‘Dove’s dumb body wash bottles are an answer to a question nobody asked‘ in The Washington Post

- Eleanor Margolis, ‘Thanks Dove! Now I will finally stop comparing myself to the perfect form of a soap bottle‘ in The New Statesman

- Becca Andrews, ‘As a Girl, I Went Through Abstinence Ed. As a Woman, I’m Trying to Understand the Damage Done.‘ on Mother Jones

- Jenny Landreth, ‘Heroic British women swimming figures who deserve statues‘ in The Guardian

- Sady Doyle, ‘“Stealthing” Is Not a Trend. It’s Sexual Assault‘ in Elle

- Amy Hatvany, ‘I Taught My Son How Not to Be a Rapist‘ in Harper’s Bazaar

- Jess Zimmerman, ‘The Monstrous Female Ambition of the Harpy‘ on Catapult

- Danielle Dash, ‘Serena Williams and Black Pregnancy‘ on Danielle Dash

- Hawa Allen, ‘Becoming Meta‘ on Longreads

Society and Politics:

- Zoe Samudzi, ‘Who Are You and What Do You Really Know?‘ on The New Enquiry

- Masha Gessen, ‘The Autocrat’s Language‘ in The New York Review

- Maya Binyam, ‘Spell-Check Nation‘ on The New Enquiry

- Carla Bruce-Eddings, ‘Creating a Community for My Black Daughter‘ in The Cut

- Carole Cadwalladr, ‘The great British Brexit robbery: how our democracy was hijacked‘ in The Guardian

- Jessica Wapner, ‘Austin, Indiana: the HIV capital of small-town America‘ on Mosaic

- Nesrine Malik, ‘I Am Not Your Muslim‘ on NPR

- Javaria Akbar, ‘In praise of smelly food‘ on The Pool

- Rebecca Solnit, ‘Facing the Furies‘ in Harper’s

- Katherine Fidler, ‘How it feels when your research is used to justify disability benefit cuts‘ in The New Statesman

- Chimene Suleyman, ‘Britain is still searching for Maddie – why don’t we care about missing children of colour?‘ in International Business Times

- Julia Rampen, ‘View from Paisley: How the Conservatives are wooing Labour’s Scottish heartlands‘ in The New Statesman

- Rachel Monroe, ‘How rich hippies and developers went to war over Instagram’s favourite beach‘ in The Guardian

- Emma Green, ‘How Two Mississippi College Students Fell in Love and Decided to Join a Terrorist Group‘ on The Atlantic

- Irin Carmon, ‘If abortions become illegal, here’s how the government will prosecute women who have them‘ in The Washington Post

- Nina Caplan, ‘Beware of tea: the cuppa has started wars and ruined lives’ in The New Statesman

- Jess Phillips, ‘May says this is about stability. She should meet my constituents‘ in The Guardian

- Santilla Chingaipe, ‘Hair and social inclusivity‘ on The Saturday Paper

- Megan Garber, ‘Are We Having Too Much Fun?‘ in The Atlantic

- Ruth Whippman, ‘Work/life integration? No, thanks – I’d rather have balance‘ on The Pool

Film, Television, Music, Art, Fashion and Sport:

- Caity Weaver, ‘Dwayne Johnson for President!‘ in GQ

- Anna Leszkiewicz, ‘“I’m only human”: the rise and rise of male singers who cannot take criticism‘ in The New Statesman

- Helen Lewis, ‘From wars to power ballads: the geopolitics of Eurovision‘ in The New Statesman

- Sophie Gilbert, ‘What Does a Girlboss Look Like?‘ on The Atlantic

- Jude Rogers, ‘Bananarama – the ultimate British girl band – is back‘ on The Pool

The interviews/profiles:

- Joanna Ruocco in The Paris Review

- Dorothy Allison on Lenny

- Meg Howrey on Electric Literature

- Patricia Lockwood on The Pool, Literary Hub and The Observer

- Alyssa Cole on Jezebel

- Jess Arndt in The Cut

- Claudia Rankine on Literary Hub

- Dana Schwartz on Electric Literature

- Hala Alyan on Electric Literature

- Stephanie Powell Watts on Literary Hub

- Doree Shafrir on Hazlitt

- Edan Lepucki on The Millions

- Scaachi Koul on Hazlitt

- Olivia Sudjic in Vogue

- Irenosen Okojie on Medium and Minor Literature[s]

- Fiona Melrose on Short Story Day Africa

- Naomi Alderman in The New Statesman

- G. Willow Wilson in The New Yorker

- Kate Tempest in The Guardian

- Paula Cocozza in The Hackney Gazette

- Anne Elizabeth Moore on Literary Hub

- Claire Cameron on The Millions

- Lise Gaston on All Lit Up

- Sally Rooney on Short Story Award

- Lidia Yuknavitch on The Rumpus

- Monica Youn on Dive Dapper

- Morgan Parker in The New Yorker

- Amy Liptrot on Literary Hub

- Diane Schoemperlen on Queen Mob’s Tea House

- Jessie Burton in The TLS

- Aliette De Bodard on SciFiNow

- Elizabeth Strout in The New Yorker

The regular columnists:

- Ijeoma Oluo on The Establishment

- Lucy Mangan in Stylist

- Roxane Gay in The Guardian US

- Caitlin Moran in The Times

- Ella Risbridger in The Pool

- Sali Hughes in The Pool

- Bim Adewunmi in The Guardian

- Sophie Heawood in The Guardian

- Eva Wiseman in The Observer

- Tracey Thorn in The New Statesman

- Chimene Suleyman and Maya Goodfellow on Media Diversified

- Josie Pickens on Ebony

- Lizzy Kremer on Publishing for Humans

- Juno Dawson in Glamour

- Louise O’Neill in the Irish Examiner

- Jendella Benson on Media Diversified

- Lola Okolosie in The Guardian

- Sarah Gerard, ‘Mouthful‘ on Hazlitt

- Books by Women We’d Love to See in English on Literary Hub