WITMonth is at an end, but I wanted to finish with a piece about two of the most important books I’ve read in the last month, both of which are about teenage girls/young women.

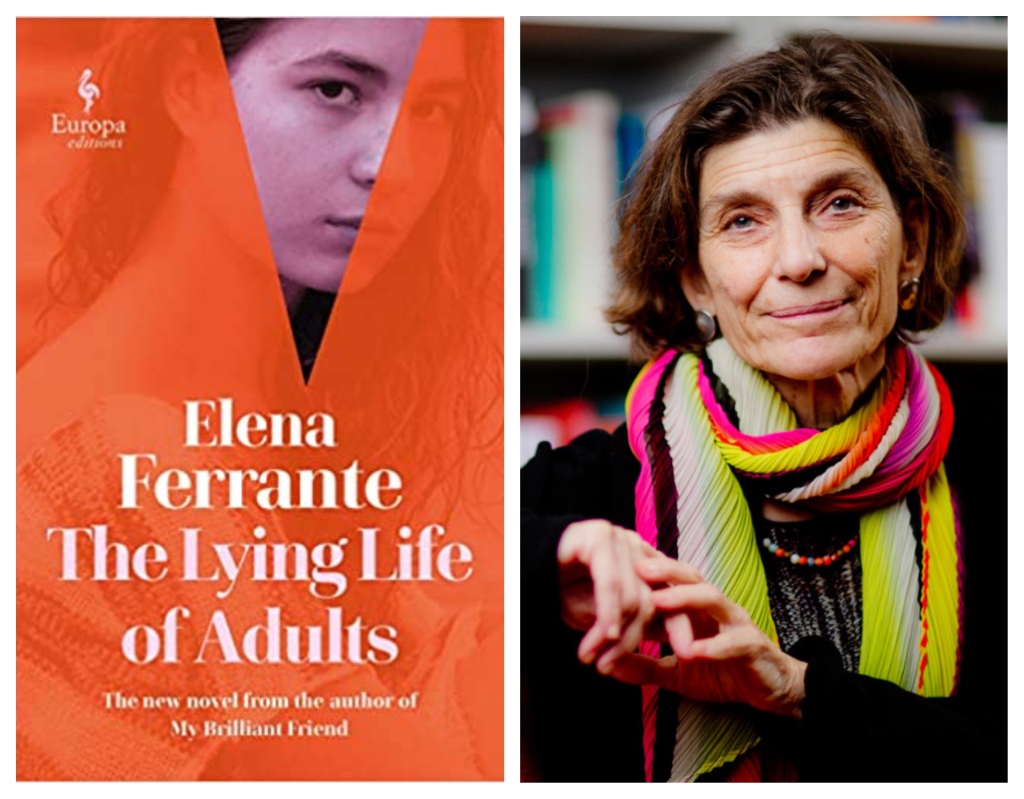

The Lying Life of Adults – Elena Ferrante, translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein (Europa Editions)

What happened […] in the world of adults, in the heads of very reasonable people, in their bodies loaded with knowledge? What reduced them to the most untrustworthy animals, worse than reptiles?

Teenage Giovanna overhears her father calling her ugly, or at least comparing her to his sister Vittoria, which Giovanna translates as being called ugly. In my house the name Vittoria was like the name of a monstrous being who taints and infects anyone who touches her. Giovanna’s at an age where this comment pierces, and it shifts her view of her father who she believed adored her.

Giovanna’s never met her Aunt Vittoria due to a family fallout after Vittoria had an affair with Enzo, a married police sergeant and the father of three children. Now her curiosity’s been heightened, Giovanna asks her parents if she can meet Vittoria and eventually, they agree. The introduction of Vittoria into her life opens up the world for Giovanna. In a literal sense due to the need to travel to a different part of Naples, where she also meets new people and makes new friends, including Enzo’s children, and in a metaphorical sense as Giovanna becomes more aware of the complexities of life.

Vittoria is a bitter woman. Enzo has been dead for seventeen years and, despite befriending his widow and her children, she has never got over it. She veers between pulling people into her confidence and then violently rejecting them, her insecurity resulting in cruelty.

Encouraged by Vittoria, Giovanna thinks she sees a moment of something between her mother and another man, but the truth turns out to be much more explosive. Ferrante’s depiction of that moment during adolescence when you realise your parents are fallible and not the deities you’ve believed them to be is perfect. Not only does Giovanna discover that the adults around her tell lies but, as she moves towards adulthood, she also begins to tell more lies herself, attempting to cover up who she’s with and what she’s doing.

Ferrante’s world is immersive; the characters utterly believable. Her exploration of power dynamics in families, between friends, and between men and women/teenage boys and girls is nuanced and engrossing. The Lying Life of Adults also has one of the best final lines ever written, gloriously capturing how it feels to step into adulthood. One of the most anticipated books of the year, Ferrante fans will not be disappointed.

Dead Girls – Selva Almada, translated from the Spanish by Annie McDermott (Charco Press)

In 1986, Selva Almada was thirteen. In the back garden of her parents’ house, she heard the news on the radio that a teenage girl, nineteen-year-old Andrea Danne, had been stabbed through the heart while she slept in her bed. For Almada, it was the moment she realised that nowhere was safe.

For more than twenty years, Andrea was always close by. She returned with the news of every other dead woman. With the names that, in dribs and drabs, reached the front pages of the national press, and steadily mounted up: María Soledad Morales, Gladys McDonald, Elena Arreche, Adriana and Cecilia Barreda, Liliana Tallarico, Ana Fuschini, Sandra Reiter, Caroline Aló, Natalia Melman, Fabiana Gandiaga, María Marta García Belsunce, Marela Martínez, Paulina Lebbos, Nora Dalmasso, Rosana Galliano.

More than twenty years later, Almada comes across fifteen-year-old María Luisa Quevedo’s story; missing for several days in 1983, raped, strangled and her body dumped on wasteland. This is followed by the story of twenty-year-old Sarita Mundín who disappeared in 1988 and whose remains were found on the banks of the Tcalamochita river. Several things link the three cases: all of the victims were teenage girls/young women; all three of them were killed in the 1980s in Argentina, and all three crimes remain unsolved.

Almada sets out to write about these girls: to gather the bones of these girls, piece them together, give them voice and then let them run, free and unfettered, wherever they have to go. She researches their lives and deaths; talks to people who were close to them; visits the towns they grew up in.

The other commonality in these stories is, of course, the men in these girls’ lives. There is an unsurprising amount of violence, as well as behaviour that is unacceptable but tolerated. However, although Almada reports details of these men, the focus remains clearly on the girls.

Dead Girls is a sucker-punch of a book. While it hinges on the three girls Almada chooses to spotlight, the book’s other primary function is to bear witness to some of the other girls and women who’ve been murdered. The book is littered with their names in a way that reminded me of Maggie in Evie Wyld’s The Bass Rock suggesting that we should be able to see the bodies of the women who’ve been killed by men as we go about our daily lives; that there’s a serial killer who murders women, and society ought to be putting a stop to him.

While the content of Dead Girls is often difficult to read, it is an important and – unfortunately – a necessary book.

All review copies provided by the publishers as stated.