At the end of 2019, I challenged myself to read 100 books from my own shelves. What I meant by from my own shelves were the books that had been sitting there some time, often for years. I was fed up of not getting to books that I knew I wanted to read because there was always something shiny and new in front of me. The pandemic helped, of course; losing most of your work and being forced to stay at home will do that. I finished the 100 in early December. Here are the ones I really really loved.

The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake – Aimee Bender (Windmill)

I thought this would be twee, I was so wrong. The story of a girl who realises she can taste people’s emotions; the story of her brother who begins to disappear. It’s about trauma and depression and it’s perfect.

The Western Wind – Samantha Harvey (Jonathan Cape)

A Brexit allegory disguised as a Medieval whodunnit. Utterly compelling.

Fleishman Is in Trouble – Taffy Brodesser-Akner (Wildfire)

A soon-to-be-ex-wife and mother disappears. A terrible soon-to-be-ex-husband who thinks he’s great has his story narrated by his ‘crazy’ friend. A piercing look at heterosexual marriage and a send-up of the Great American Novel. Longer review here.

Things we lost in the fire – Mariana Enriquez (translated by Megan McDowell) (Granta)

Dark, dark, dark stories. So haunting, so brilliant.

Exquisite Cadavers – Meena Kandasamy (Atlantic)

A Oulipo style novella showing how fiction can be created from life, but it isn’t the same thing. Longer review here.

Ongoingness: The End of a Diary – Sarah Manguso (Graywolf Press)

Manguso wrote a daily diary until she had her first child. This is full of ideas of letting go which are so brilliant I copied many of them on to Post-Its and stuck them above my desk. It’s published by Picador in the UK.

we are never meeting in real life – Samantha Irby (Faber)

Irby is my discovery of the year. Her essays are laugh-out-loud funny and entertaining but they are also about her life as a working class, disabled Black woman with a traumatic childhood. Revolutionary.

Heartburn – Nora Ephron (Virago)

Funny; good on cooking and marriage. Devastating final chapter.

Fingersmith – Sarah Waters (Virago)

Clever crime novel about class, the art of theft and pornography. Superb structure. A masterpiece.

The Chronology of Water – Lidia Yuknavitch (Canongate)

Yuknavitch’s non-chronological memoir about the fifteen lives she has lived. It’s about dying (metaphorically), swimming (literally and metaphorically) and living (literally). It fizzes.

Bear – Marian Engel (Pandora)

The headline is this is a book about a woman who has sex with a bear. It’s really about female autonomy. It’s being republished in the UK in 2021 by Daunt Books.

Magic for Beginners – Kelly Link (Harper Perennial)

Kelly Link is a genius. These stories are so rich in detail; she takes you from a situation that seems perfectly normal to a wild, subverted world that also seems perfectly normal. Incredible.

Parable of the Talents – Octavia E. Butler (Headline)

The novel that predicted a president who would aim to ‘Make America Great Again’. It’s as much the story of a mother / daughter relationship formed under significant trauma as it is the story of a country at war with itself. Longer review here.

Copies of The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, Fleishman is in Trouble, Exquisite Cadavers, we are never meeting in real life, The Chronology of Water and Parable of the Talents were courtesy of the publishers as listed. All others are my own copies.

Kindred is the story of Dana, a 26-year-old black woman living a few miles from LA with her white husband, Kevin. It’s 1976. As they unpack the boxes in their new home, Dana begins to feel dizzy and sick. She’s pulled from 1976 to 1815 where a young white boy, Rufus, is drowning. Dana saves him but then is almost shot by the boy’s father. As she stares down the barrel of his rifle, she travels forwards to 1976 where Kevin tells her she’s only been missing for a few seconds.

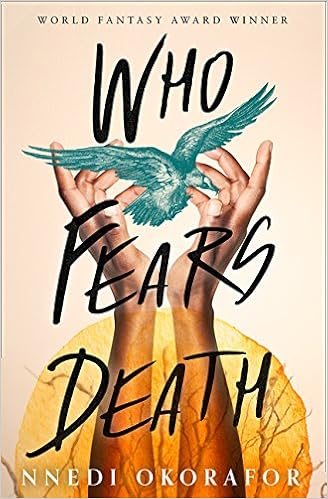

Kindred is the story of Dana, a 26-year-old black woman living a few miles from LA with her white husband, Kevin. It’s 1976. As they unpack the boxes in their new home, Dana begins to feel dizzy and sick. She’s pulled from 1976 to 1815 where a young white boy, Rufus, is drowning. Dana saves him but then is almost shot by the boy’s father. As she stares down the barrel of his rifle, she travels forwards to 1976 where Kevin tells her she’s only been missing for a few seconds. Onyesonwu is the protagonist of Who Fears Death, the title being the meaning of her name in an ancient language. Onyesonwu is an Ewu – the product of rape – and has been shunned because of it. The novel begins with her telling us that the father who raised her, who looked beyond what she was to who she was, died. In the four years since his death a lot has happened. She dictates this to an unknown scribe with a laptop during the two days she has left to live.

Onyesonwu is the protagonist of Who Fears Death, the title being the meaning of her name in an ancient language. Onyesonwu is an Ewu – the product of rape – and has been shunned because of it. The novel begins with her telling us that the father who raised her, who looked beyond what she was to who she was, died. In the four years since his death a lot has happened. She dictates this to an unknown scribe with a laptop during the two days she has left to live.