If you read my interview with Sarah Ladipo Manyika, author of the Goldsmiths Prize shortlisted Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun, you might have noticed that one of the books listed in her current favourites wasn’t published at the time of writing. That book, Longthroat Memoirs: Soup, Sex, and Nigerian Taste Buds by Yemisi Aribisala is now available, published by Cassava Republic. Aribisala’s aim in writing it is to bring Nigerian cooking to a wider audience via a mix of cultural history, memoir and recipes. It’s beautifully written and I’m delighted to share with you a special piece, not in the book, in which Aribisala looks at Christmas in Nigeria.

Kanda for Christmas

On the morning of Christmas Eve of 2009, my neighbour’s husband came around to express nervous concern. He had opened the pots and found nothing but Kanda (pomo, long-sufferingly boiled cowhide) there. Was he to take this as a sign of what Christmas day held? Everyone found his concern hilarious. We laughed so hard we couldn’t breathe. Deep down we were as nervous as he was. There was a cloud of misery over Christmas in Calabar that year. It was tall, deep, wide, dense as the humidity that cloaked many of the days in the month of December. As if to commemorate the eccentricity of that year, even Harmattan winds failed to bring expected freshness in the mornings and evenings. The air was hot and heavy from morning till night, day after day, distended by the incessant grinding of running generators boring into our brains already overwhelmed with keeping count of the amount of diesel being guzzled by hard-working engines. Someone brought a food hamper round and then came back for it a couple of hours later because he’d made a mistake – it wasn’t for us. We desperately needed something to laugh out loud about, so we laughed at my neighbor and his nervousness about eating Kanda for Christmas. We kept him handy for when reality wanted to steal on us, to remind us there was hunger at our gates and in the city and everywhere. We cried out aloud and crowned the declarations with more laughter – “God in your infinite mercy, please don’t let Kanda be what is on the menu this Christmas.”

What did I end up eating that Christmas? I ate everything. If it was possible to eat the sofa, I would have done so. Slow roasted chicken marinated with coriander, cloves, cardamom, hot-peppers, garlic, ginger, raisins and coconut milk; the gamiest most tender he-goat oven-cooked with garam masala spices eaten with fluffy bowls of basmati rice; barbecued pork cooked with Cameroonian peppers on an outside grill, the aroma of charred fresh meat and sweet peppers carrying all the way to Akpabuyo; creamy potato salad made creamier by soft yielding potatoes; sweet fat plantains roasted on the grill alongside the meat, too sweet and soft to be boli eaten with groundnuts, not sweet and soft enough to be mashed into stew then scooped up into your mouth; more plantains fried with sprinklings of cinnamon and pepper, drenched in pineapple juice-then fried in coconut oil. There was freshly juiced pineapples and ginger root served with chilled sprigs of mint; supple clouds of fufu eaten with briskly cooked Afang and Kundi; mugs of Milo made up with peppermint teabags eaten with staggeringly drunk Christmas cake; freshly brewed coffee laced with Irish-cream eaten with almond, raisin and coconut flapjacks. Some mornings, breakfast was hot puff-puffs fried in chili-pepper infused oil eaten with a whole cafeterie of black coffee.

In other words, the more I thought of world hunger and local hunger and recessions and depressions, the more I evoked the shell-shocked expressions in people’s faces in the market place, the weary despondency of light in Goshen and darkness everywhere else in Egypt. The cracks in buying power and dinner plates between the haves and have-very little and have-nots; the middle-class falling into the crevices and disappearing altogether the more I ate. I engaged all the different joys and rationales of eating: comfort eating, Christmas entitlement eating, eating in company so that people don’t feel bad that you are not eating, eating the left-overs so they don’t spoil, eating what the neighbour sent round because you can’t very well throw good food away. And, let’s not forget that I am a food writer so I must eat to fulfill my purpose, Thank God!

The peppery puff-puffs, Cameroonian coffee, barbecued pork and potato salad were courtesy of my neighbours whose pots had hitherto only exhibited Kanda till Christmas Eve. My neighbour’s wife’s love for Kanda was passionate – so passionate that the rolls of cow-hide had to feature in most of her pots of soup throughout the year. But at Christmas, that love had to be abruptly filed as inordinate for everyone’s sake in order not to attract the misfortune hanging around waiting to pounce. Beneath the under-toned laughter we ate and gave thanks.

The most interesting aspect of Nigerian Christmas fare for me is the snubbing of the food we would normally eat, for food that we consider festive even if the preferred food makes no real festive sense. If you served the most spectacular Afang soup at Christmas, the most beautifully dressed, stuffed roast turkey with the most expensive ingredients in the world, it would still come second place to Rice and Chicken, just rice and chicken. There must of course be stew. Nigerian Christmas stew is 70% psychological fare and 30% gastronomical fanfare. The psychological and gastronomical balance for Christmas stew, rice and chicken adds up and exceeds the psychological and gastronomical balance of roast turkey plus everything under the sun to go with it. For many years, I wanted to write a Christmas column for the Nigerian, to explain how we feast with modesty, to commend the uncomplicatedness of our requirements of rice, lots of rice, rice flowing down the streets, rice bags rolling everywhere with hens running around the place to become chicken, stew, bottles of Guldier and Star Beer, a new wrappa, dresses for little girls, new shirts and trousers for little boys. I wanted to say that the emphasis was on being with family: sitting around with them and laughing a lot, slaughtering chickens and stewing them into juicy chunks on steaming white rice, visiting people and eating their food and letting them come over and eat yours.

And then my good intentions got run over by the years, and by successive governments and economic downturns and inflation and grief. The truth is that the food writer at Christmas is a hoggish callous character – she must emphasise the glory of food regardless of other people’s hunger. She must contemplate food, eat food, intellectualise gluttony and suppress guilt. The gathering of words together in one place to eulogise food is ever more so irritatingly elitist when contrasted with real life, so much more vividly callous in times of national celebration. If we thought things were bad in 2009, in 2016, the Christmas stew became officially endangered from the middle of the year, when a basket of tomatoes became more expensive than a barrel of crude oil. Then rice because of high foreign exchange rates became unaffordable. In essence even our chosen simple fare became imperiled, and with it our willingness to entertain guests and burden others with our visits. If we laughed at my neighbour in 2009 at his snubbing of Kanda, in 2016 we can’t laugh because we understand that food is no longer a “safe topic”, a topic that we can laugh at; a topic we can resort to when there are no other uniting colloquialisms, when soccer has failed and politics is unapproachable. We are expecting famine in 2017, and whole parts of Nigeria are already starving, the images of starvation on social media is heartbreaking, mandatory and crushing.

What is one to do with the obligation to celebrate Christmas in light of all this strong painful awareness? I’m all for gratitude for well-cooked stewed Kanda as a good starting point. The simplicity of meals reassures me that I am alive. How lucky the person is who loves stewed Kanda in the first instance – they won’t feel hard done by if required to eat it. They will be happy eating it whenever – Christmas, New Year, Monday, Friday, Sunday. I suspect my neighbour’s wife had spent a few lean Christmases before her marriage and had learnt to be happy with little or with plenty on her plate. Whatever manner of Christmas she thus encountered after those lean ones, she met them with happiness and gratitude.

This year I’m not going to pretend that my job requires the eating of everything in sight. I’m not going to eat the sofa, the cushions and the remote controls for the television. In honour of the insufficiently acknowledged resilience of Nigerians, the long fought battle of retaining basic happiness and good hope in-spite of many dire twists and turns of life; in consideration of those in real danger of starvation, in commending those still willing to share a meal with a neighbour, in earnest prayers that God in his infinite mercies won’t let the coming year be one of famine for the sake of us all, I’m not writing a Christmas column for the food writer, but for that woman, my neighbour who circuitously predicted that in seven years our self-entitlement would have to be curtailed, our snobbery discarded, our people embraced tighter. She intimated so long ago that we would have to eat less, laugh at ourselves more, give away more and eat Kanda with thanks.

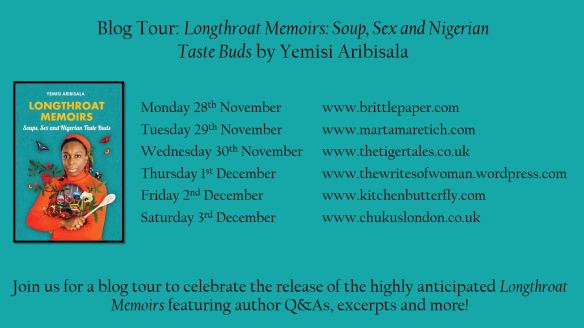

Huge thanks to Yemisi Aribisala and Cassava Republic for the guest post. This post is part of a blog tour. Please do visit the sites listed below to read more from and about this wonderful book.